The leaders of Timor-Leste and Indonesia agreed in August 2015 to renewed and wider discussions, covering both

maritime and land boundaries. Timor-Leste commenced talks with Indonesia for permanent maritime boundaries in

September 2015. The small fraction of the land boundary that has not yet been settled will be finalised shortly.

In the initial consultations on maritime boundaries in 2015, Indonesia and Timor-Leste jointly developed a set of

principles and guidelines and a work plan for the negotiations. Both States affirmed that the position of a permanent

maritime boundary should be negotiated in accordance with international law, particularly UNCLOS.

Preliminary technical meetings were held in Bali in December 2018, and in Singapore in February 2019, with

discussions to continue when the COVID-19 situation permits.

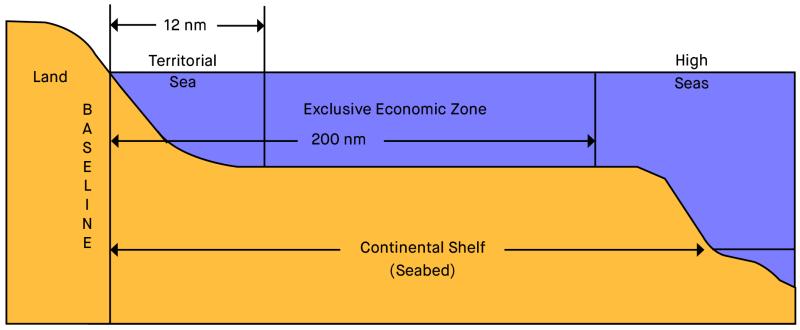

The territorial sea extends up to 12 nautical miles from a State’s baselines (which are generally drawn along the low-water line of the coast). States have control of the air-space above the territorial sea and the water column, seabed and subsoil below.

The Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) extends up to 200 nautical miles from a State’s baselines. Within that zone, States have the right to exploit living and non-living resources in the seabed, subsoil and water column, including petroleum resources and fisheries.

The continental shelf extends to at least 200 nautical miles from a State’s baselines. In some cases, a State can claim an extended continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles where there is a ‘natural prolongation’ of the shelf. States can exploit resources that lie in the seabed and subsoil of the continental shelf.

Where neighbouring States (with opposite or adjacent coasts) have overlapping claims to EEZ or continental shelf rights, UNCLOS requires that they reach agreement on a permanent maritime boundary based on international law, in order to achieve an equitable solution.

Determining permanent maritime boundaries is a matter of national priority for Timor-Leste, as the final step in establishing its sovereignty as a newly independent State. For the people of Timor-Leste, securing rights to the nation’s maritime territory is a continuation of their long struggle for sovereignty and independence. Maritime boundaries will allow Timor-Leste to better explore and develop petroleum and fisheries resources, encourage business and investment, and add to the resource revenues in the sovereign wealth fund, which is a fund dedicated to building a prosperous future for the people of Timor-Leste.

“Securing maritime boundaries is a matter of sovereignty for the people of Timor-Leste.”

UNCLOS imposes an obligation on States to define permanent maritime boundaries with neighbouring States by agreement. In cases of overlapping claims (i.e. where there is less than 400 nautical miles between neighbouring coasts), international law generally takes the approach that a median or equidistance line should be drawn between them, with adjustments made for relevant circumstances (if any), in order to reach an equitable solution. This is known as the “equidistance/relevant circumstances approach” to maritime boundary delimitation. In most cases, the equitable solution under international law is an equidistance line, sometimes with adjustment as necessary to take into account relevant circumstances.

The leaders of Timor-Leste and Indonesia agreed in August 2015 to renewed and wider discussions, covering both maritime and land boundaries. Timor-Leste commenced talks with Indonesia for permanent maritime boundaries in September 2015. The small fraction of the land boundary that has not yet been settled will be finalised shortly.

In the initial consultations on maritime boundaries in 2015, Indonesia and Timor-Leste jointly developed a set of principles and guidelines and a work plan for the negotiations. Both States affirmed that the position of a permanent maritime boundary should be negotiated in accordance with international law, particularly UNCLOS.

Preliminary technical meetings were held in Bali in December 2018, and in Singapore in February 2019, with discussions to continue when the COVID-19 situation permits.

Indonesia has ten neighbours with whom it shares maritime boundaries. Of these, Timor-Leste and Palau are the only countries with whom Indonesia is yet to reach any maritime boundary agreement and it has started discussions with both.

After a hard-fought struggle, Timor-Leste and Australia signed a Maritime Boundary Treaty which established permanent maritime boundaries in the Timor Sea on 6 March 2018. This followed the successful conclusion of the compulsory conciliation process. Both the Timor-Leste and Australian governments have committed to ratifying the Treaty as soon as possible. Once the Treaty is ratified, it will become legally binding.

The Maritime Boundary Treaty sets, for the first time, permanent maritime boundaries between Timor-Leste and Australia in the Timor Sea. The Treaty secures a median line in the Timor Sea with only a slight adjustment to achieve an equitable result as required by international law.

Most of the median line is ‘all purpose’, meaning it encompasses both the ‘continental shelf’ (which entails rights to exploit seabed resources, such as petroleum) and the ‘exclusive economic zone’ (which entails rights to exploit resources in the water column, such as fisheries). Under the agreement, the Greater Sunrise resource is shared by Timor-Leste and Australia, with the majority sitting in Timor-Leste’s maritime area and the majority of revenue flowing to Timor-Leste.

The agreed maritime boundary puts all of the resource fields in the former Joint Petroleum Development Area (JPDA) within Timor-Leste’s continental shelf. This means that, unlike the previous revenue-sharing arrangements, title to all future revenue from the Bayu-Undan and Kitan fields will be transferred to Timor-Leste. In the west, the agreed seabed boundary runs to the west of the previous JPDA and results in the Buffalo petroleum field transferring from Australia to Timor-Leste.

The agreement on maritime boundaries is comprehensive and final, however, part of the seabed boundary is provisional and subject to automatic adjustment upon certain events. The provisional seabed boundaries in the north-east and the west could swing outwards to meet the trilateral points agreed in the upcoming negotiations with Indonesia. This means that, depending on the outcome of negotiations with Indonesia, Timor-Leste could look to extend its maritime area even further.

Compulsory conciliation is a procedure under UNCLOS (Annex V, Section 2) in which a panel of conciliators assists State parties to try to reach an amicable settlement of their dispute. This procedure can be used in circumstances where no agreement has been reached between neighbouring States and one State has made a declaration excluding the jurisdiction of binding dispute settlement bodies on maritime boundaries, as Australia has done.

Compulsory conciliation can help a State like Timor-Leste try to resolve a maritime boundary dispute when it has no other option. The conciliation is conducted by a panel of five independent conciliators, known as the conciliation commission. For more information on compulsory conciliation, see the [fact sheet].

The Maritime Boundary Treaty sets out a Greater Sunrise Special Regime for the joint development, exploitation and management of the resource. Timor-Leste, Australia and the relevant petroleum contractors are engaging in a separate process to negotiate and agree on commercial terms for the development of Greater Sunrise.

For more information about the development of Greater Sunrise, visit the ANPM website.

Before Timor-Leste’s independence was restored in 2002, the Timor Sea Arrangement was agreed between Australia and the United Nations, which negotiated on Timor-Leste’s behalf during the period of United Nations transitional administration. The Arrangement set out temporary resource-sharing arrangements and established a Joint Petroleum Development Area in the Timor Sea.

That treaty was replaced with the near-identical Timor Sea Treaty, agreed between the Governments of Australia and Timor-Leste, and signed on 20 May 2002 – the restoration of independence day.

Soon after the Timor Sea Treaty, Australia and Timor-Leste entered into special, provisional arrangements relating to the Greater Sunrise area, known as the Unitisation Agreement.

The Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea (CMATS) treaty was signed on 12 January 2006. It was during negotiations on this treaty that Australia allegedly spied on Timor-Leste’s negotiating team.

As part of the confidence-building measures agreed during the conciliation process, on 10 January 2017 Timor-Leste exercised its right to unilaterally terminate CMATS. The termination of CMATS came into effect three months later, on 10 April.

The Timor Sea Treaty therefore applies in its original form as an interim arrangement before the Maritime Boundary Treaty is ratified and enforced. In preparation for the ratification of the Treaty, Timor-Leste and Australia have been working with contractors operating in the Joint Petroleum Development Area to finalise transitional arrangements, allowing for the relevant fields to transfer to Timor-Leste once the Treaty is in force.

This website is hosted by the Maritime Boundary Office of the Council for the Final Delimitation of Maritime Boundaries to allow readers to learn more about Timor-Leste’s pursuit of permanent maritime boundaries. The Council for the Final Delimitation of Maritime Boundaries and the Maritime Boundary Office do not accept any legal liability for any reliance placed on any information contained in this website (including external links). The information provided is a summary only and should not be relied upon as legal advice. The information and views expressed in this website and in any linked information do not constitute diplomatic representations and do not limit or otherwise affect the rights of the Council for the Final Delimitation of Maritime Boundaries, the Maritime Boundary Office or the Government of Timor-Leste. The views expressed in any linked information do not necessarily reflect the views of the Council for the Final Delimitation of Maritime Boundaries, the Maritime Boundary Office or the Government of Timor-Leste.

GFM is the acronym for “Gabinete das Fronteiras Marítimas”, which is the Portuguese translation of Maritime Boundary Office.